Wars have been significant in the history of Nacogdoches for the changes that they cause in the town and inthe lives of Nacogdoches's citizens. To view or print a brochure about Wars in Nacogdoches, please click the following link War in Nacogdoches Brochure, or for more information, please continue reading.

Nacogdoches War Memorial located at the Nacogdoches County Courthouse

The Civil War

The slavery debate, which led to the Civil War, began early in Texas. Although the Mexican Government strictly forbade it, Anglo settlers brought their slaves with them from the United States to Coahuila y Texas.[1] On September 15, 1829, the President of Mexico, Vicente Guerrero, issued an order abolishing slavery throughout Mexico. The Texans resisted and eventually Guerrero overturned the order. However, seven months later the Law of April 6, 1830, reinstated the ban. Texans managed to keep their slaves by claiming that they were contracted workers, and though they felt the institution was cruel and immoral, the Mexican officials could not deny that slavery was profitable.[2] Yet not all Texans owned slaves, as many citizens could not afford or had no need for them.[3] The state census of 1847 showed that Nacogdoches County had a population of 4,172 individuals, of whom 1,228 were enslaved.[4] John J. Hayter owned the highest number of slaves, sixty-four.

The Texas Revolution was fought in 1836 in part due to the desire of Texans to return to the Constitution of 1824, which gave more power to the state government than the federal government in Mexico City.[5] After annexation, Texans realized that they had just willingly handed their power back over to another federal government. Although President Sam Houston detested the idea of secession, he had to concede when a majority of Texans voted to secede from the Union to join the Confederacy.[6] In Nacogdoches, 317 individuals voted in favor of secession while ninety-four voted against secession.[7] Among the reasons Texans gave for seceding was the belief that the states' rights to make decisions for their citizens should supersede the national government's, that the Northern and Southern economies were not compatible, and that the two regions had conflicting values systems.

Regardless of what motivated Texans to join the Confederacy, it is estimated that between 68,000 and 90,000 Texans signed up to fight in the Civil War.[8] Texans fought on both sides of the Civil War, though the majority served in the Confederate army. Approximately 2,132 whites, forty-seven blacks, and an unknown number of Mexican Texans fought on behalf of the Union.[9] Assisting the Union was dangerous in Texas. Sixty-five Unionists attempted to cross the Rio Grande into Mexico but were stopped by state troops and thirty-five of them were killed. In addition, fifty Union sympathizers were hanged in Gillespie County and thirty-nine more were executed in Gainsville.[10] Racial minorities in Texas were driven to join Union forces in spite of the risk because they opposed slavery, to satisfy grudges against whites who had treated them unjustly, and in hopes that the Union would win the war and that their lives would improve.[11]

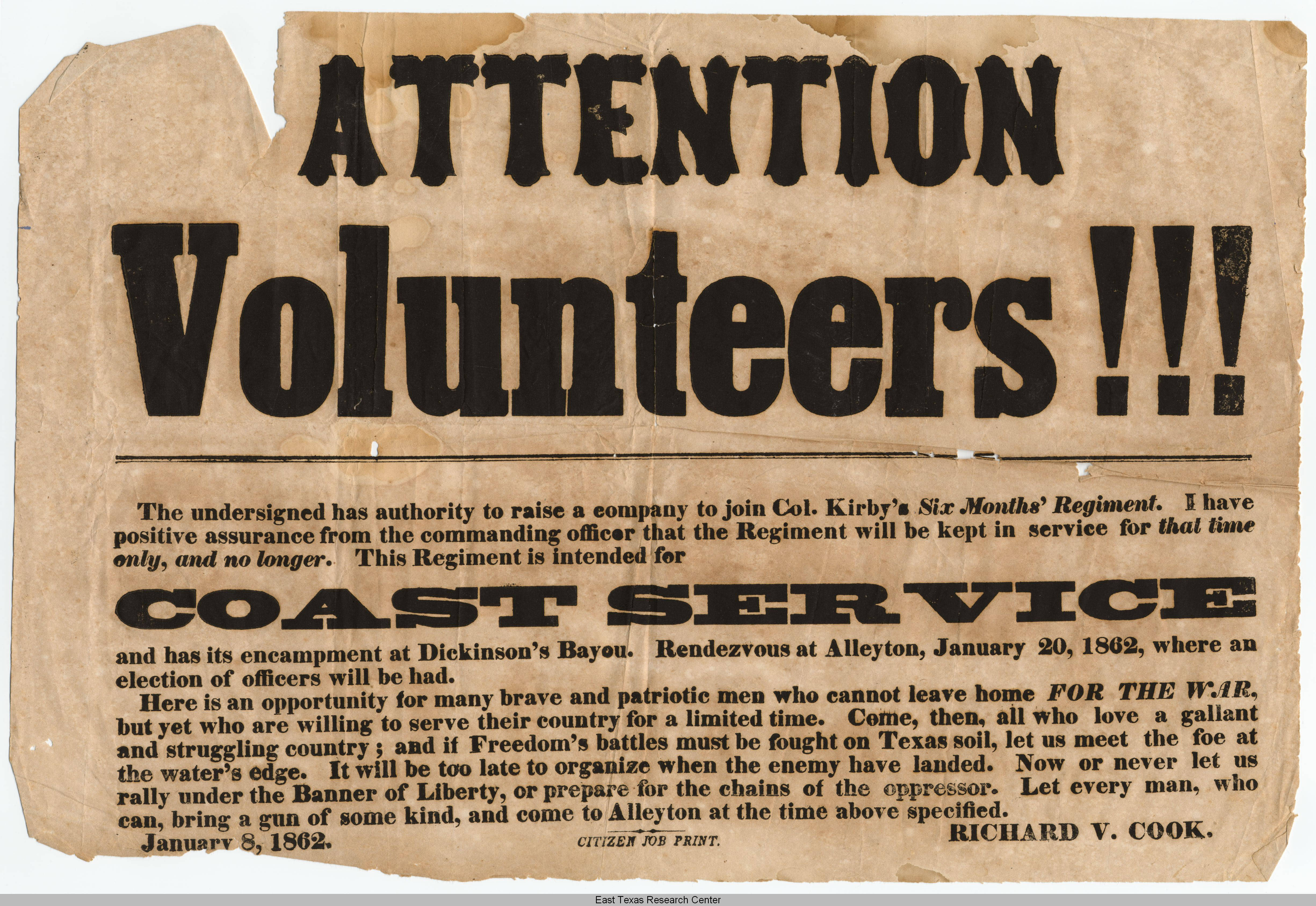

Call for Confederate Volunteers

Nacogdoches men also took part in the Civil War. Calls went out for volunteers and locals signed up for both the Confederate and Union Armies.[12] A muster roll from March 12, 1862, shows that thirteen companies of volunteers were from Nacogdoches County. It is estimated that about 1,500 men from Nacogdoches volunteered for Confederate service. It is unknown whether men from Nacogdoches fought for the Union, possibly because it was dangerous to be found out as a Union sympathizer so they remained anonymous or because many of the records remaining today are of Confederate pensions. While no battles took place in Nacogdoches, a Confederate hospital was set up Washington Square to serve those injured in the Texas battles of Sabine Pass, Galveston, and Sabine Crossroads near Mansfield.[13]

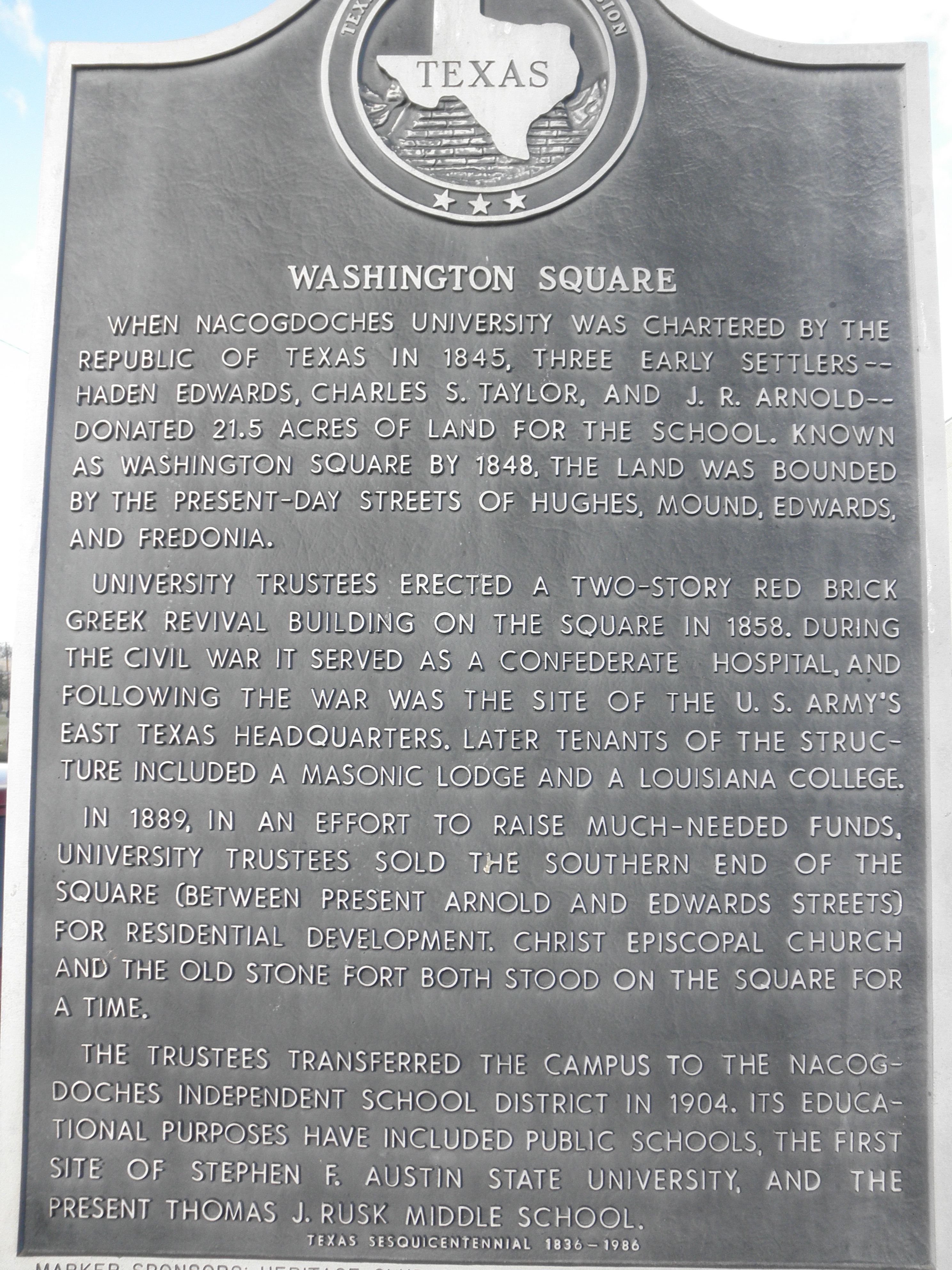

Washington Square Historical Marker

The Nacogdoches economy, much like the rest of the South, suffered during the war due to blockades and the shortage of men at home causing decreased production.[14] According to James A. Day who lived during the Civil War, 1860 was one of the driest years he had ever seen and the next year the war began.[15] The people of East Texas had gotten many of their supplies from Shreveport but the markets there closed due to a lack of supplies. After that, families had to learn to make everything they needed for the home, they began to grow wheat for flower, sorghum for sugar, barley for coffee, and hunted and gathered from the woods. When asked if it was difficult to get supplies after the war stared and the Southern ports were blockaded, Sophia Shaw Peevey, another individual who lived in East Texas during the war stated that

"It was not exactly a problem; it was an impossibility. We just did not get them. We learned to raise what we could, and what we could not raise or make at some we did without. It all sounds funny now but it was not exactly funny in those days. Still, people were accustomed to hard work and long hours. They were in the habit of making the best of things, consequently, there was no complaining or grumbling, though there was enough sadness and grief to make up for it. My neighbors were all women whose husbands, fathers, brothers, had gone off to fight. In the whole neighborhood there was only one man and he was very old and not able to be of much assistance…We raised some corn, a little cotton, also chickens, hogs, and a few milk cows, so that we had plenty to eat and wear…but as for sugar, coffee, drug medicine, these things were unobtainable…what few medicines we had we made ourselves from plants and herbs…we could not even buy pins and needles, so you may be sure we were extremely careful with those things…I made all my sheets and blankets from cloth that I spun myself…the things I made for myself were either white or gray so it was necessary to dye many of them. There were certain kinds of weeds from which we could obtain gray, brown, blue, and black colors. We could get a farily good grade of red dye from a certain kind of red clay, and also from poke berries."[16]Nacogdoches was not exempt from Union occupation during Reconstruction.[17] The soldiers built an encampment along Banita Creek and served as a policing force, though some citizens felt that they served more as a reminder of the South's defeat. An epidemic of dysentery passed through Nacogdoches at this time and led to the death of eighteen to twenty-one of the Union troops, who were buried at Old North Church Cemetery. In 1863 the state of Texas passed the Relief Act, which provided money to assist the dependents of men who were away from home serving the Confederacy.[18] Though Charles S. Taylor prepared a list of families in need, no money was ever appropriated by the state to help those families.

After the war, not only did Nacogdoches's veterans return but also other families arrived to make their home in Nacogdoches county.[19] On May 12, 1899 the Texas State Legislature passed the Pension Act providing pensions for disabled and indigent veterans and their widows who had served the Confederacy.[20] The Confederate veterans of Nacogdoches continued to meet with each other for reunions until at least 1924.[21]A revision was made to the Pension Act in 1925, which changed the terms in regards to who could receive a pension but it continued to deny assistance to Union veterans.

The Spanish-American War

Though Texans did not see much action in the Spanish-American war, it was not due to a lack of enthusiasm on their part.[22] After the U.S.S. Maine was sunk in the Havana harbor in February of 1898, President McKinley called for volunteer regiments to fight the Spanish in Cuba.[23] Of the forty-eight units of the Texas Volunteer Guard, thirty-eight volunteered, including Nacogdoches's own Stone Fort Rifles.[24] The Stone Fort Rifles became Company B of the Second Texas Volunteer Infantry Regiment.[25] The company left Camp Mabry in Austin on May 20, 1898, and travelled to their first camp in Mobile, Alabama.[26] In a letter to the local newspaper, one of the soldiers reported that the Company B (The Stone Fort Rifles) had a reputation for being one of the best disciplined companies with one of the loudest and fastest charges as well as keeping the neatest quarters.[27] The people of Nacogdoches were very kind to the soldiers by supplying them with much needed items such as shoes, socks, underwear, blankets, and soap.[28] Though these items were greatly appreciated, the men reported that swampy conditions of their camp in Mobile made it miserable to carry around their equipment sacks. Their equipment included a canteen full of water, haversack with two tin plates, a cup, knife, fork, spoon, extra clothes, shoes, and other necessary items: a wool blanket, half of a tent, one tent pole, four pegs, a poncho, their nine pound Springfield rifle, fifty cartridges, and a bayonet.[29]

The Stone Fort Rifles

On June 25, 1898, the U.S. Army transported the men from Mobile to Miami, which they nicknamed "Camp Hell" because their duties consisted mainly of clearing land in the heat.[30] The Army's decision to station so many men in Miami was shortsighted because the men lacked appropriate uniforms and cooking supplies.[31] In addition, the soldiers had only bacon to eat for the first ten days of their stay. Diseases such as malaria, dysentery, and typhoid fever were rampant among the men, and the Stone Fort Rifles suffered their only casualty of the war due to disease.[32] The next stop on the Stone Fort Rifles' tour was in Jacksonville, Florida, where they stayed from August 1, 1898, until returning to Dallas in September of 1898.[33] Though the Stone Fort Rifles did not fight in the Spanish American War, over their ninety-year history they received many awards and accolades for their participation in drills, encampments, and parades in East Texas and across the state.[34]

World War I

Before being drawn into World War I, many in the United States felt very separated from the war because it was taking place across the Atlantic and did not yet affect them directly.[35] While President Wilson encouraged Americans to remain neutral, citizens were divided on whether to enter the war and on which side they should enter if they did.[36] The discovery of the Zimmerman Telegram in 1917 ended this debate. The German Foreign Secretary, Arthur Zimmerman, sent the letter to Germany's ambassador in Mexico asking him to persuade Mexico to join Germany in attacks against the United States.[37] These attacks would include encouraging raiders, such as Pancho Villa, to cause as much trouble as possible in along the border of the United States. [38] The letter asked Mexico to uphold their arrangement and once Germany won, they would restore all of Mexico's former territories in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona would be restored.[39] Americans were infuriated that Germany was trying to bring the war to their own back door and focused all of their energy on helping the allies. Nearly 200,000 Texans either volunteered or were drafted for service in the Army, Navy, or Marines.[40]

Victory Liberty Loan Poster

Although relations between African Americans and Whites were still tense, nearly one-fourth of the men who volunteered or were drafted were African Americans. While some African Americans saw the war as an opportunity to show their patriotism and their place as equal citizens of the United States, others viewed the war and it's message of bringing democracy and freedom to other countries as hypocritcal.[41] Due to segregation and continuing racial prejudice, these men served in all African American units that were often under supplied, under trained, continued to receive poor treatment from whites, and were often placed in service units rather than combat units.

In addition to the men, about 450 women from Texas served as nurses while twenty-five thousand women from across the United States travelled to Europe to provide food and supplies for the military, serve as phone operators, provide entertainment, and work as journalists.[42]

Over 5,000 Texans were killed in the Great War. One-third of these wartime deaths were due to the 1918 Spanish influenza outbreak. A plot at the front of Oak Grove Cemetery of Nacogdoches was set aside for those killed in the war.

WWI Plot at Oak Grove Cemetery

The war made it necessary for Texans to maximize their output of crops and goods while minimizing the amount that they used in the home. Both white and black women at home helped the war effort by participating in wartime fundraising organizations, which promoted purchasing Liberty and Victory bonds and war savings stamps.[43] They also participated in food conservation by using as little fat and sugar as possible while also taking part in wheatless Mondays and Wednesdays, meatless Tuesdays, and porkless Thursdays and Saturdays.

The American economy profited from the war because it supplied most of the Allies' weapons and food.[44] While many families were low on money and living as minimally as possible, those in the lumber industry of East Texas were profiting from the Great War as prices for lumber soared to two or three times their usual amount.[45] Another group that profited from the war were farmers, who could demand higher prices for their crops, which were purchased by the U.S. Government.[46]

German Barbed Wire from WWI

With so many of the local men were away at war, it became necessary for over one million women to take up jobs and fill roles traditionally held by men.[47] Like racial minorities, American women hoped that the social changes they experienced during the war would serve as a turning point in their own status in society.[48] This change in traditional gender roles eventually led to the women's suffrage movement and altered the way women viewed themselves and their role in society.[49]

The Texas legislature instituted many acts to help veterans during and after the war. They devised ways to compensate soldiers for their service, to provide protection for veterans and their property, to establish sanatoriums, to assist in finding jobs, and to provide free tuition at state colleges.[50] In 1932 the House of Representatives passed the World War I Veterans Bonus Bill, which granted each veteran one thousand dollars.[51]

To hear oral history interviews of World War I veterans, select one of the following names:

George Burton - to hear about his experiences in WWI and life in the military

John Moore - to hear about his experiences in WWI, trench warfare, and military life

Jess Pettey - to hear about his experiences in WWI, military life, railroads, and trench warfare.

Francis M. Sterling - to hear about his experiences in WWI, prisoners of war, the railroad, and veterans benefits

World War II

About 750,000 Texans either volunteered or were drafted into the military to serve in World War II.[52] This number included 12,000 women volunteers, who served in all branches of the military.[53] According to Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox, Texas contributed the largest percentage of men to the military than any other state.[54] World War I veteran John Moore stated that he did not exactly understand what the war was really about, he "felt like we were forced into it and it was the thing to do, and, of course, there was lots of patriotism, even the boys who were drafted were patriotic…I have no idea when I joined that army that I would be in war."[55] Another veteran, George Burton of Nacogdoches, stated that he entered the military because he wanted to travel and see some of the world.[56] These Texans fought in both the European and Pacific theatres of war and many received accolades for their service as individuals and groups.[57] Thirty-three Texans received the Medal of Honor for their service during the war.[58] 22,022 Texans were killed or mortally wounded during World War II.

Nearly one third of those who served in the war were racial minorities. Mack Hopkins, a veteran of World War II stated that most everything that he did while in the military was segregated, "separate but equal, even though it wasn't equal."[59] Hopkins was fortunate in making it into the Air Force, while most African Americans were assigned to labor battalions or working in mess halls. Mexican Texans also answered the call to serve and though they also faced discrimination in the service, five went on to receive the Medal of Honor and another won the Bronze Star.[60]

Like in World War I, Texans did what they could to help the war effort by purchasing war bonds, rationing, growing Victory Gardens, and hosting scrap iron drives.[61] War brought wealth to the state through military bases, petroleum plants on the Gulf Coast, steel mills, aircraft factories, shipyards, and rubber plants.[62] Also like World War I, American agriculture fed both the people back home as well as the Allied troops.[63] Due to the lack of men to perform labor, women and minorities stepped into jobs that had previously been unavailable to them, such as driving trucks and building ships, and with their help kept the war time economy running and contributed to a higher standard of living for those Texans who remained at home.[64]

Prisoners of war also aided the economy of many areas of Texas. Texas held the largest population of prisoners of war totaling about 50,000 including primarily Germans but also Japanese and Italians.[65] Prison camps eventually went from a policy of operating at maximum security of the prisoners to maximum utilization of the prisoners when local communities needed a source of manual labor.[66] Camps in East Texas were located in Chireno, San Augustine, Huntsville, Mexia, Tyler, Lufkin, Center, and Alto.[67] Prisoners of war were desperately needed in East Texas after an ice storm damaged many of the trees and the lumber was feared lost unless harvested quickly. POWs continued working in the lumber industry where they performed hard manual labor including cutting down trees, trimming them to size, and loading the wood onto carts.[68] Though the prisoners of war were in Texas under less than desirable terms, many found their time here to be pleasant and returned after the war.[69]

Sgt. Tony Ball and a German POW at Camp San Augustine

The enrollment at Stephen F. Austin State Teacher's College fell from nine hundred students in 1940 to around three hundred in 1944.[70] The school began searching for a way to aid in the war, which would help the university to keep its doors open.[71] The school became the home of the Women's Army Corps on February 15, 1943. Volunteers had to be between the ages of twenty-one and forty-four, have no dependents, be at least five feet tall and over one hundred pounds, and in good health.[72] WACs trained for six weeks in administrative services and learned skills such as stenography, translation, typing, telegraphing, and clerical services.[73] The women were paid fifty-four dollars a month, which surprisingly, was the same as enlisted men.[74] The WAC classes took up so much space that university classes had to be scheduled around them whenever and wherever space was available.[75] The WAC program ended at SFA in 1944 and is credited with keeping the college open during the war years.[76] Another life saver for SFA was when Congress passed the Servicemen's Readjustment Act or the GI Bill, which encouraged returning servicemen to go to college. In 1946 1,000 students were enrolled at SFA, three years later that number had grown to 1,500, and thirty percent of those were veterans.[77]

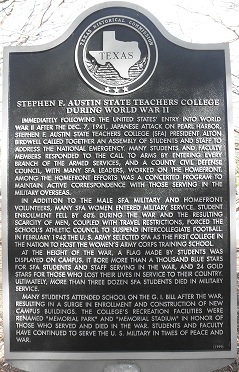

Stephen F. Austin State Teachers College during WWII Historical Marker

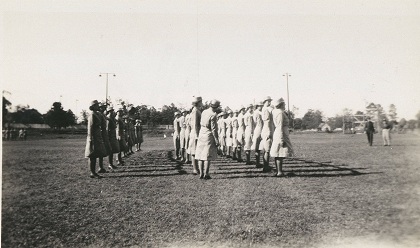

Woman's Army Corps Unit at SFA

To hear an oral history interview of a World War II veteran, select one of the following names:

Perry Bonner - to hear about his experience in WWII

Milo Cockerham - to hear about his experience in WWII and military life

Mack Hopkins - to hear about his experience in WWII, aircraft, Tuskegee airschool, and segregation during the war

James Wilson - to hear about his experience in WWII, aircraft, air warfare, and subsequent wars

Vietnam

Texas, much like the rest of the United States, was divided over the Vietnam War.[78] While World War II had been front page news in The Daily Sentinel, the Vietnam war was hidden in the middle of the paper until the United States became involved.[79] Unlike prior wars where locals hurried to volunteer and did all that they could to aid the war effort, the Vietnam War was received with skepticism and protest.[80] Unlike World War I and World War II, the population of Stephen F. Austin State University maintained a steady student population, thanks in part to men avoiding the draft by attending college.[81] Apart from soldiers and their families, the lives of Nacogdoches's citizens remained mostly the same.[82]

In 1975 SFA made national headlines for the widespread streaking occurring on campus.[83] When asked why he believed that students were streaking, Professor of Communication Jim Towns stated that he thought that they were protesting everything from war to feminism.[84] During and after the war, Vietnamese refugees began arriving in Texas, which soon ranked second in the nation after California for the number of refugees. East Texas did not receive the large numbers of Vietnamese that the coastal areas and Houston did but the Luong family grave marker in Oak Grove Cemetery is evidence that Nacogdoches was not untouched by this mass migration. To locate the Luong grave at Oak Grove Cemetery, visit www.preserveamerica.sfasu.edu/OakGrove and enter their name in the search criteria.

Vietnam War Protest at SFA

Images

- Nacogdoches War Memorial located at the Nacogdoches County Courthouse on the southwest corner of Main Street and South Street, Nacogdoches, Texas.

- Call for Confederate Volunteers, January 8, 1862, Daughters of the American Revolution Records, accessed January 24, 2013, East Texas Research Center, Stephen F. Austin State University, Nacogdoches, Texas, http://digital.sfasu.edu/cdm/ref/collection/EastTexRC/id/3880 .

- Washington Square Historical Marker located at 515 North Mound Street, Nacogdoches, Texas.

- Stone Fort Rifles, Photograph Collection 1890-1899, East Texas Research Center, Stephen F. Austin State University, Nacogdoches, Texas, http://digital.sfasu.edu/cdm/ref/collection/EastTexRC/id/9 .

- "For Home and Country, 1918" Burton Crossland collection, East Texas Research Center, Stephen F. Austin State University, Nacogdoches, Texas, http://digital.sfasu.edu/cdm/ref/collection/EastTexRC/id/12119 .

- World War I Plot at Oak Grove Cemetery, Nacogdoches, Texas.

- Barbed Wire - German World War I, Stone Fort Museum, East Texas Research Center, Stephen F. Austin State University, Nacogdoches, Texas, http://digital.sfasu.edu/cdm/ref/collection/StoneFort/id/177 .

- Sgt. Tony Ball and German Prisoner at Camp San Augustine, Photograph Collection, East Texas Research Center, Stephen F. Austin State University, Nacogdoches, Texas, http://digital.sfasu.edu/cdm/ref/collection/EastTexRC/id/11975 .

- Stephen F. Austin State Teachers College During World War II located on the campus of Stephen F. Austin in front of Ralph Steen Library.

- Women's Army Corps Units, Photograph Collection 1940-1949, East Texas Research Center, Stephen F. Austin State University, Nacogdoches, Texas, http://digital.sfasu.edu/cdm/ref/collection/EastTexRC/id/6564 .

- Vietnam War Protest, Photograph Collection 1970-1979,East Texas Research Center, Stephen F. Austin State University, Nacogdoches, Texas, http://digital.sfasu.edu/cdm/ref/collection/EastTexRC/id/11954 .

References