Environmental science alumnus builds career restoring ecosystems

Story by Sarah Fuller '08 & '13

On a county road outside of Hallsville, pine trees, native grasslands and improved grasses sway in the brisk breeze of an early summer day. Amid the chatter of multiple avian species, Dr. Eric Anderson '98 & '00 pauses to point out the call of a dickcissel, a migratory bird species that relies on grassland habitats such as this. Surprisingly, the beauty of this pastoral scene is just a few short miles from bustling Interstate 20. This fact, however, pales in comparison to Anderson's revelation that the seemingly undisturbed landscape was once a 150-foot-deep coal mine spanning more than 1 mile.

"When we take someone to a mine site, tell them that it has been mined, and they say 'no way,' that is the ultimate success standard," Anderson said. "The goal for us is that you never know we were there."

For nearly two decades, Anderson has worked to ensure just that — first as an award-winning reclamation specialist and environmental manager with North American Coal and now as the president of Mitigation Resources of North America.

Founded in 2017, Mitigation Resources of North America is part of NACCO Natural Resources' family of companies that specializes in everything from full-service mining operations to land reclamation and wetland and stream mitigation.

Anderson acknowledges the coal industry isn't always positively perceived, but it's working to better communicate the full story.

"The industry is regulated by the U.S. Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act, and the standards say we have to leave the land as good as or better than it was before it was mined," Anderson explained. "Once we've mined, the land is leveled back to its approximate original contours. From there, it becomes a big farm — either in forestry, native grasses, improved grasses for livestock, or fish and wildlife habitat."

Coal mine reclamation ensures the transition of cavernous, working mines to seemingly undisturbed landscapes of forests, native grasslands or improved grasses supporting fish, wildlife and livestock. Photos were taken at different sites within the Sabine Mine.

Following this reclamation, environmental parameters, such as soil and water quality and land productivity, are regularly monitored.

During his time at North American Coal's Sabine Mine, Anderson estimates he helped reclaim close to 8,000 acres.

In 2011, the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department awarded Anderson and the team at Sabine Mine with the Lone Star Steward Award for their successful efforts to restore northern bobwhite quail habitat. According to the TPWD, the state agency responsible for overseeing and protecting wildlife and their habitats, Texas has seen a 75% decline in bobwhite quail populations since 1980. This is due in large part to critical habitat loss through urban development and land conversion.

"We built back the native grasses they rely on," Anderson said. "We have a large population of bobwhite quail on the mine site just south of Hallsville. Any morning, you can ride out and listen to the various coveys of quail all around you."

The Texas Historical Commission also recognized Anderson's efforts to preserve Texas' history and cultural heritage with a 2012 Award of Merit in Historical Preservation. Anderson said archaeological assessments are required when moving to a new mining area. Depending on what is uncovered, archaeologists determine if further study is needed. In this case, Anderson said the significance of the location was obvious.

In addition to a large Caddo burial mound, archaeologists uncovered evidence of a surrounding village.

"We uncovered enough that, as a company, we knew there was no way we should impact it," Anderson said. "We took a big chunk of the mine site and donated it to the Archaeological Conservancy, so it's forever protected. It was just the right thing to do."

Artifacts uncovered during the archaeological assessment were returned to the Caddo Nation, and an on-site ceremony to honor ancestors was led by tribal members.

Following the centennial of North American Coal's founding, Anderson said the company began discussing ways to help ensure another 100 years of successful operation.

"We took the core set of skills we have in the company and looked for ideas in new fields we could branch into," Anderson said.

Given North American Coal's vast experience in land reclamation, as well as stream and wetland mitigation, Anderson said management saw an opportunity to expand into the rapidly growing stream and wetland mitigation banking industry. Thus, Mitigation Resources of North America was born.

Although Anderson was a part of the team that pitched the mitigation-based business proposal to North American Coal's board of directors, he wasn't expecting to immediately take on the top leadership role.

"I kid you not, I got up and went to the bathroom," Anderson said with a laugh. "When I came back, our project lead said, 'We've decided you're going to run the business.'"

The immediate promotion may have been a surprise, but Anderson was undoubtedly qualified. After earning a Bachelor of Science in environmental science and Master of Science in forestry from SFA, Anderson earned a doctoral degree in soil science from North Carolina State University before beginning his career with North American Coal.

After consulting with his wife, Charlotte '00, who graduated with a Bachelor of Business Administration and a Master of Professional Accountancy from SFA, Anderson decided to take on the challenge of building Mitigation Resources of North America from the ground up. To establish a team, Anderson called on Leland Starks '07, fellow SFA environmental science alumnus and then-environmental specialist with North American Coal.

"Leland actually worked for me as an intern while he was attending SFA," Anderson said. "On a drive back from a conference we attended, I told him, 'I don't know how, when or where, but we're going to work together.'"

Five years later, the team has expanded to roughly 20 staff members with projects located across Texas, the Southeastern U.S. and as far north as Pennsylvania. The diversity of academic and professional expertise among staff members introduced by Anderson reflects the breadth of the mitigation field.

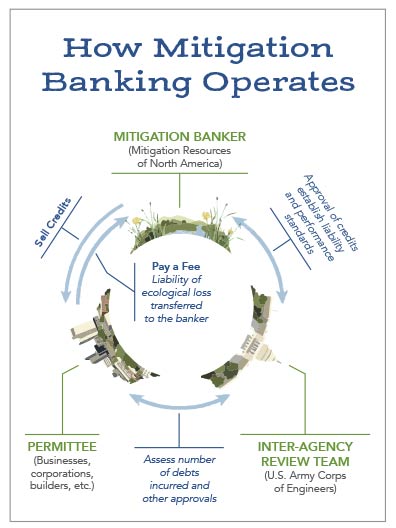

In accordance with the Clean Water Act, any unavoidable damage as the result of federally permitted projects that affects wetlands or streams must be compensated for through the restoration, enhancement or creation of other wetlands or streams. This can be done through restoration on-site or through the purchasing of mitigation credits.

"The mitigation banking business allows a company like us to have a mitigation bank," Anderson explained. "The bank basically means we own a piece of property that has a credit ledger of restored stream credits that entities can purchase to replace what they impacted."

To create these credits, which are administered by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, companies like Mitigation Resources of North America ecologically restore denuded landscapes and waterways utilizing the expertise of ecologists, stream engineers and others.

Before: Waterway that has been channelized and overtaken by nonnative or invasive vegetation. After: Reestablished natural stream sinuosity and native vegetation along waterways. Photos courtesy of Mitigation Resources of North America.

Throughout NACCO's history, Mitigation Resources of North America and its sister companies have planted more than 8.8 million trees, restored more than 1,400 acres of wetlands, reestablished more than 54 miles of streams, and planted more than 19,000 acres of native grasses.

Anderson attributes many of his career achievements to the professional foundation established at SFA under the direction of Dr. Kenneth Farrish, director of SFA's Division of Environmental Science.

"The hands-on work we did at SFA created a success-driven system," Anderson said. "To be honest with you, a vast majority of the credit, as I see it, goes to Kenneth Farrish. He was a huge mentor, and a lot of things he did set a foundation that really created who I am today."

Axe ’Em, Jacks!

Axe ’Em, Jacks!